Struggle & Repression - From Soweto to New York

The life of black South African artist DUMILE in drawings and Sculpture 1960-1991

"One day I was in the Township with this driver and we went past a line of men who were all handcuffed. I don't know what for, maybe for having no pass or something. Anyway the driver said, 'Why don't you ever draw things like that?' I didn't know what to say. Then just when I was still thinking, a funeral for a child came past. A funeral on a monday morning. You know, all the people in black on a lorry. And as the funeral went past those men in handcuffs, those men watched it go past, and those with hats took off their hats. I said to the guy I was with, 'That's what I want to draw!' "

(Simon, 1968:43)

Dumile, unknown as he is, remains a major and key figure in history of Modernism in South Africa. In the 1960's he emerged from the Township of Soweto in Johannesburg along with a generation of highly creative and dynamic artists, musicians and creatives. Among those individuals were African Jazz pioneers Hugh Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim, and a great number of the group went on to forge international careers overseas.

The Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 was the impetus for most to go into exile. For Dumile that was the year he was invited to exhibit at the Haenggi gallery in the city of Johannesburg. From 1960-1968 he created some of the most powerful images for Modern South Africa, before himself having to leave.

Bill Ainslie in 1967:

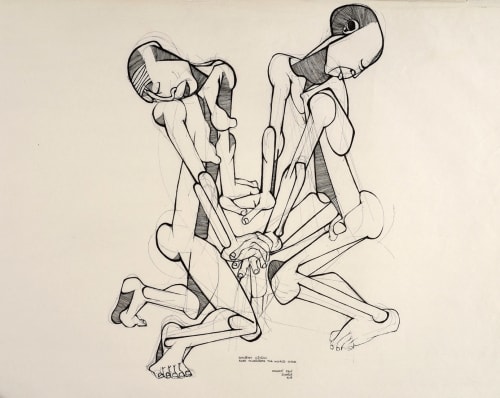

"Dumile took the raw material of his life in Soweto… and translated it into work in a manner, which revealed a capacity to face unflinchingly the most frightening extremities of human desperation and cruelty without spilling over into sentimentality or overblown expressionism. His originality led to a new style of drawing in South Africa, but I have not found anybody equal the ferocity and compassion of his work."

Dumile's rise from township artist to local celebrity was quick and added to his enigma. The local journalists came out with quotes such as: "The Star of 66", "He rose from the dead to become a genius", "At the beginning of the year no one had heard of him. He grew up a waif - nobody's child, educated in the tough school of Johannesburg's Township slums. He is simply known as Dumile…. he bears the scars of numerous stabbings…. He one was once left for dead on a mortuary slab…"

He went on to influence many of the artists of the day. South Africa's most well know contemporary artist William Kentridge recalls "As a teenager I went to Bill Ainslie's studio… Dumile made remarkable strong, dynamic drawings, either in ballpoint on a small scale or in charcoal on a large scale. That was the first time that I understood the power of figurative, large scale charcoal drawings; that they could be so striking… he had the capacity to express things on a scale that I thought drawings could not achieve. He is the key artist who influenced me."

This early success led to several museum acquisitions, including 'Railway Accident 1966', one of four works acquired by the South African National Gallery. Interestingly, this piece was exhibited at the 1967 Sao Paolo Biennale and then not widely seen until 2002 when Okwui Enwezor selected the work for the landmark exhibition 'The Short Century', when it travelled to Chicago, New York, Berlin and Munich. Adding to the myth of this untaught Township artist, no one really knew when he was born. At the Sao Paolo Biennale he was described as "He is about 26 years old."

Success however came at a cost. The notoriety alerted him to the authorities, who above all wanted to quash the rumours of Dumile's association with white art patrons. They slapped him with restrictions and ordered him to return to his hometown thus forcing him into exile, literally a choice of life or death.

Exiled from 1968-1991, between London and New York, Dumile's life was one of survival and lost memories. He continued to draw and sculpt and had some exhibitions, including at the Camden Arts Centre, London in 1969. His social network was fellow exiled artists, musicians and with that freedom fighters and the ANC. John Matshikiza: "I heard about Dumile when Hugh Masekela's album 'Home is where the Music Is' was released. I was living in Lusaka at the time… Thabo Mbeki told me that the artist was an extraordinary person. 'You must meet him when you go to London, he sits at the back of the pub to draw and talk all the time' he told me the man's name was Dumile."

Despite the truly heroic efforts of some curators, such as Steven Slack who curated the 1988 ground breaking show at Johannesburg Art Gallery called 'The Neglected Tradition Towards a New History of South African Art 1930-1988', which included black artists such as Dumile, his works were seldom exhibited or seen in South Africa or in other Institutions.

Dumile died in 1991 in New York in exile.

The efforts of Albie Sachs and others including Moeletsi Mbeki have helped set up a Dumile Foundation and to preserve and cast some of his New York pieces in bronze, which the artist never managed. He had a museum Retrospective in 2005 at the Johannesburg Art Gallery and his works are now on permanent display at the National Gallery in South Africa.

He was never a political artist, only an artist. The quote at the top of the release captures this. And from listening and reading to accounts of the other exiles it is precisely this fact that he is remembered for.