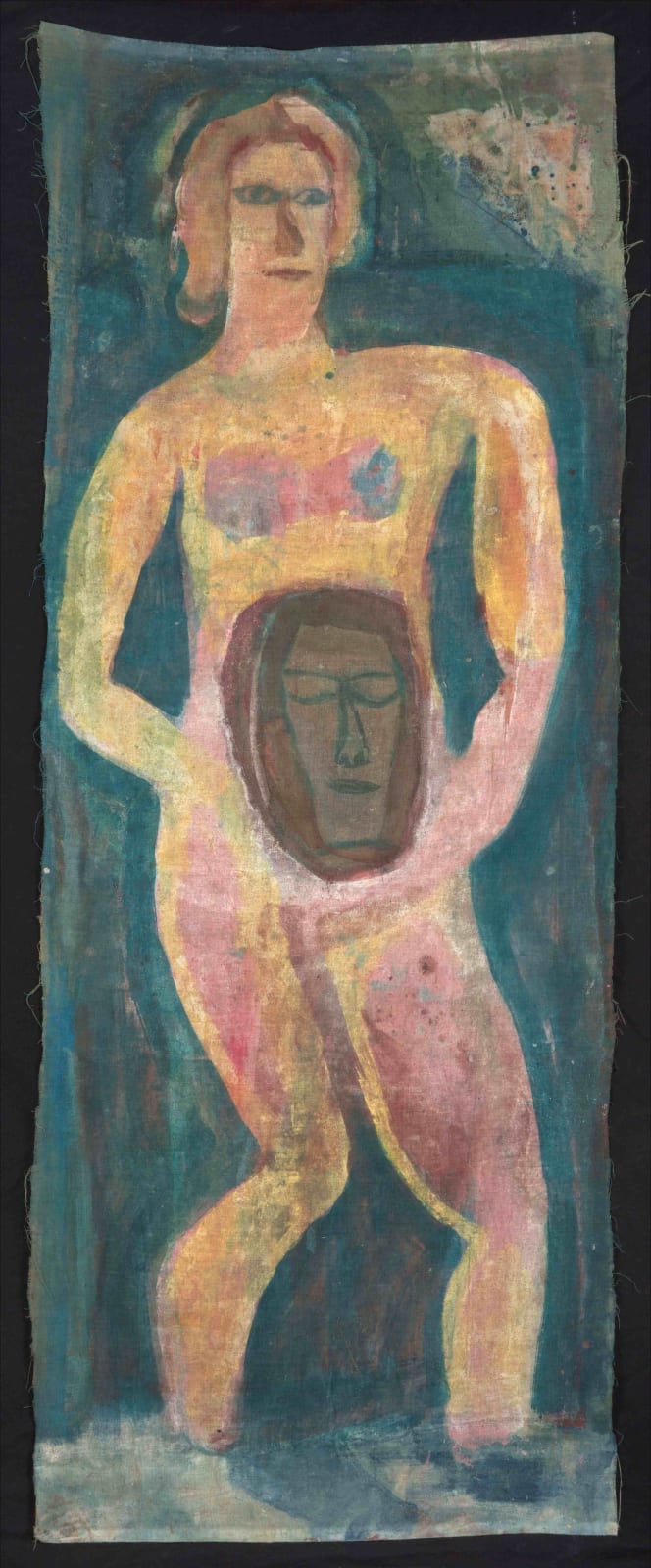

Mark Shields

Poet's Head - You are singing still, 2014

Oil on muslin

152.4 x 60.9 cm

60 x 24 in

60 x 24 in

Signed and titled on reverse

A NOTE ON THE ORIGIN OF THE SERIES I had been combining collage and paint and at one point found it useful to stick patches of muslin over the paintings...

A NOTE ON THE ORIGIN OF THE SERIES

I had been combining collage and paint and at one point found it useful to stick patches of muslin over the paintings to allow instant changes to be made. I found the texture of the muslin pleasing – it was reminiscent of the painted linen shrouds from Egypt. I decided to work directly onto loosely cut muslin fragments with diluted oil paint and found that the repainted lines and blocks of colour left ghosts and traces of previous images evoking thoughts of the image as a residue of an almost ritual act rather than mere picture-making. I made a few experimental heads and thought of The Veil of Veronica. The so-called 'image not made with hands'. Perhaps an association with the Turin shroud suggested the need to make full scale figures on narrow sections of cloth. At the same time it seemed natural that there should be a large number of these figures. Witnesses to moments of revelation, of doubt, of anxiety or of simple gratitude. And that the number should be incomplete, as though these were found objects with some obscure purpose, one of their number remaining missing.

The figure 99 became fixed in my thoughts. Christ spoke of the good shepherd who leaves the 99 sheep to go in search of the lost one. As well as its deeper spiritual implications this story reflects the artist's search. Dominated by what is yet to be discovered or revealed. The thing that remains hidden from us. A kind of negative presence. I worked on two images at once. Overlaying each on the other. Alternating and finally separating them. Two versions of the same idea, sometimes contradictory, sometimes complimentary. With single figures the tendency to broader narrative was diminished and in an attempt to create a simplified, primitive folk-image, an emblematic reading was encouraged. The whole sequence forming a kind of iconostasis. While there are little obvious religious connotations it was intended that the figures retain a sacramental character as though, like icons, they might appear to act as go-betweens, entry points to another realm. This great company forming a kind of earthbound iconostasis.

I began to think of the title Almanac as a semi-mysterious word that might encapsulate the sequence of images. The old almanacs, for all their dubious prognostications were essentially reassuring. Something to console us that our daily, weekly and monthly round had significance and meaning. Amongst the changing and unpredictable there remained changeless and certain phenomena. The seasons, the moon's cycles, sunrise and sunset, the behaviour of the tides, mysterious and otherworldly, yet certainties none the less. These old almanacs included "prophetic, hieroglyphic engravings", primitive and earthy depictions of natural activities but suggesting deeper divine or magical significance. I wanted these paintings to have something of that character. Psychological moments rescued from time and protected from forgetfulness. A past record, a present act and a future utterance all at once. I think of them as a testament to survival. A pure utterance without the interference of what people tell us 'art' should be, primal, direct and moving. My attempt at a 'Frieze of Life' - (to make humble reference to Munch).

I had been combining collage and paint and at one point found it useful to stick patches of muslin over the paintings to allow instant changes to be made. I found the texture of the muslin pleasing – it was reminiscent of the painted linen shrouds from Egypt. I decided to work directly onto loosely cut muslin fragments with diluted oil paint and found that the repainted lines and blocks of colour left ghosts and traces of previous images evoking thoughts of the image as a residue of an almost ritual act rather than mere picture-making. I made a few experimental heads and thought of The Veil of Veronica. The so-called 'image not made with hands'. Perhaps an association with the Turin shroud suggested the need to make full scale figures on narrow sections of cloth. At the same time it seemed natural that there should be a large number of these figures. Witnesses to moments of revelation, of doubt, of anxiety or of simple gratitude. And that the number should be incomplete, as though these were found objects with some obscure purpose, one of their number remaining missing.

The figure 99 became fixed in my thoughts. Christ spoke of the good shepherd who leaves the 99 sheep to go in search of the lost one. As well as its deeper spiritual implications this story reflects the artist's search. Dominated by what is yet to be discovered or revealed. The thing that remains hidden from us. A kind of negative presence. I worked on two images at once. Overlaying each on the other. Alternating and finally separating them. Two versions of the same idea, sometimes contradictory, sometimes complimentary. With single figures the tendency to broader narrative was diminished and in an attempt to create a simplified, primitive folk-image, an emblematic reading was encouraged. The whole sequence forming a kind of iconostasis. While there are little obvious religious connotations it was intended that the figures retain a sacramental character as though, like icons, they might appear to act as go-betweens, entry points to another realm. This great company forming a kind of earthbound iconostasis.

I began to think of the title Almanac as a semi-mysterious word that might encapsulate the sequence of images. The old almanacs, for all their dubious prognostications were essentially reassuring. Something to console us that our daily, weekly and monthly round had significance and meaning. Amongst the changing and unpredictable there remained changeless and certain phenomena. The seasons, the moon's cycles, sunrise and sunset, the behaviour of the tides, mysterious and otherworldly, yet certainties none the less. These old almanacs included "prophetic, hieroglyphic engravings", primitive and earthy depictions of natural activities but suggesting deeper divine or magical significance. I wanted these paintings to have something of that character. Psychological moments rescued from time and protected from forgetfulness. A past record, a present act and a future utterance all at once. I think of them as a testament to survival. A pure utterance without the interference of what people tell us 'art' should be, primal, direct and moving. My attempt at a 'Frieze of Life' - (to make humble reference to Munch).