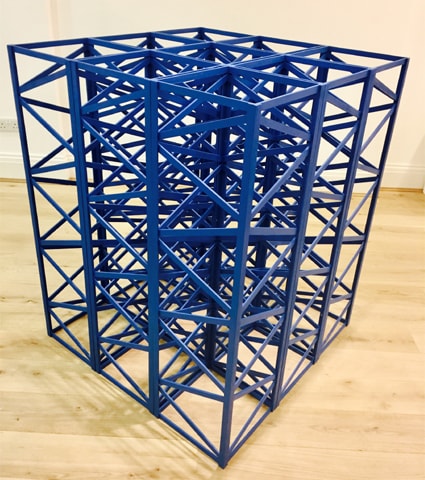

At London’s Grosvenor Gallery there was a red rectangular pillar, created from thin strips of painted wood, encasing a latticed pattern. Tall, hollow and feathery light, it looked interesting. Moving closer, it was no longer inanimate but multi-textured and alive. It had transformed into something new and fascinating. Further along was a bright blue, equally playful but larger, cube on the floor. While similar in execution (hollow, light, geometric, monochromatic) it felt radically different. It could be viewed from above and patterns emerged that were dizzying and hypnotic. At the corner of the gallery were four yellow cubes that could be arranged into numerous combinations by moving them like building blocks — a different play on a similar lattice-like structure.

By stripping sculpture down to a skeletal frame in primary colours, Araeen had aroused complex emotions through simplicity. He demonstrated that art need not be complicated to captivate and excite. These three pieces and several sketches on paper by him were exhibited alongside metal works by Anthony Caro which provided a contrast to, and a context for, Araeen’s work. Caro was the artist whose work had inspired Araeen to take up sculpture full time, and the show was aptly titled Caro Araeen: A Conversation.

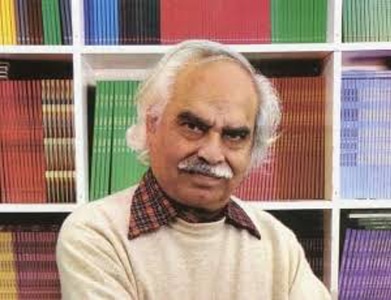

Rasheed Araeen is one of the most internationally exhibited artists this year. At the age of 82, his inner child and art innovator is still very much at play

Araeen has been at the forefront of British art for several decades and a pioneer of minimalist sculpture in Britain. He has been a leader in discussions on the nature of politics in art, and has written on art in a social, historical and racial context. He is an early advocate of post-colonial art and was the co-founder and editor of influential journals on the subject, including Black Phoenix and Third Text. The artist has published extensively as art critic, social/cultural commentator and curator and has had a profound influence on a generation of artists, writers and thinkers.

Born in Karachi in 1935, Araeen studied civil engineering at what was then known as NED Government Engineering College before turning to art in the late ’50s. Moving to the UK in 1964 he came across Caro’s work and was inspired to unlearn everything and make a “fresh start” in his own words. Combining elements of engineering design and geometric motifs, he reinvented the old and began creating simple sculptures in a style inimitably his own. By paring structures down and using bright, bold colours he liberated his art from the strictures of a colonial heritage, making it universal. Art and politics are cohesive in Araeen’s work — the minimalism, deconstruction and geometry an integral part of the narrative. More recently, he has incorporated elements of design from the golden age of Muslim civilisation — the Abbasid period.

This year Araeen is one of the most exhibited artists internationally. He is represented at the Venice Biennale and at Documenta 14 Germany/Greece, two of the most prestigious events of the year. At the Greece event, his social activism was evident; Shamiana — Food for Thought: Thought for Change is a collection of patchwork canopies inspired by the shamiana. Each evening random people were invited to sit under these and enjoy a Mediterranean inspired meal, cooked in collaboration with Organisation Earth — a Greek NGO.

At the Germany event his Reading Room is an immersive installation of sculpture, tables, wooden stools and copies of the Third Text. In addition, he has the Grosvenor show, is at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the Frieze Sculpture Park in London, and has a major retrospective at the Van Abbe Museum in Amsterdam later in the year. Hence 2017 is clearly Rasheed Araeen’s year.

At the Venice Biennale his work is the first as you enter the Arsenale, one of the two main venues. Titled Zero to Infinity in Venice, it comprises of dozens of coloured cubes in bright green, orange, pink and mauve scattered around in various combinations, some monochromatic, some mixed. The permutations could be many, and at the opening preview performers moved the cubes around, endlessly creating and recreating the work in seemingly infinite structures, evoking a childlike fascination with building blocks and colours.

The Frieze Sculpture Park is part of the Frieze Art Fair in London in October. This year the sculpture garden was set up early in the summer. Work by 23 artists including Araeen’s is on display. Summertime — The Regent’s Park is a construction in painted steel made up of bright red, yellow and blue columns placed to form a large cuboid. It stands out amid the verdant green of the park and when the sun shines through the grid, spontaneous delight is the result. At 82 Araeen’s inner child and art innovator is still very much at play.

Shahid N. Zahid is a development policy specialist with an abiding interest in art, music, theatre and film

Published in Dawn, EOS, September 24th, 2017