The idea of “looking into someone’s soul” ensured that the painting session was not a dominant process of creation and allowed her to share an equal relationship with the protagonists in her work. (Vicky Luthra)

The idea of “looking into someone’s soul” ensured that the painting session was not a dominant process of creation and allowed her to share an equal relationship with the protagonists in her work. (Vicky Luthra)A Thousand Splendid Lotuses

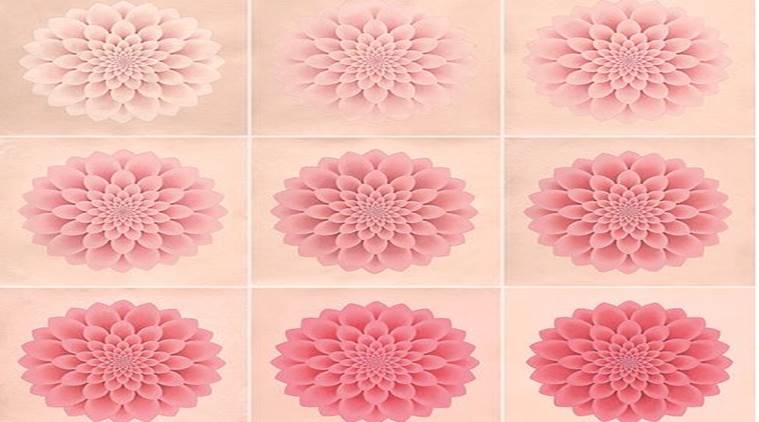

The 17 works on display are centeredaround the lotus in myriad forms as Fraser deconstructs, expands and contracts the flower in each of her canvases. She uses layers of handmade wasli paper, and pigments made from malachite and semi precious stones from Jaipur.

Written by Pallavi Chattopadhyay

The idea of “looking into someone’s soul” ensured that the painting session was not a dominant process of creation and allowed her to share an equal relationship with the protagonists in her work. (Vicky Luthra)

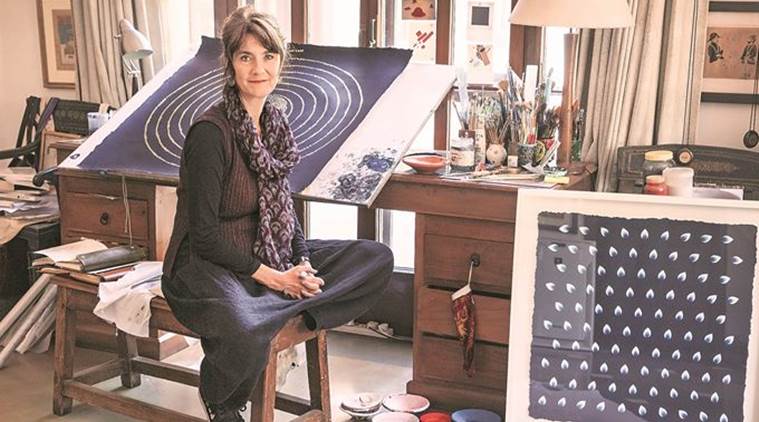

The idea of “looking into someone’s soul” ensured that the painting session was not a dominant process of creation and allowed her to share an equal relationship with the protagonists in her work. (Vicky Luthra)Long before Scottish artist Olivia Fraser gave Indian miniatures a contemporary twist by using the lotus flower, andhands and feet as central motifs, she would frequently paint people on the streets — labourers toiling away and folk musicians during performances in Rajasthan — using western watercolour techniques. She’d wait for them to catch her stare. The idea of “looking into someone’s soul” ensured that the painting session was not a dominant process of creation and allowed her to share an equal relationship with the protagonists in her work. Although theDelhi-based artist does not paint people anymore, she continues to paint eyes. The result rests in London’s Grosvenor Gallery as part of her exhibition ‘The Lotus Within’, where large eyes stare at the viewer in Darshan II, with the iris shaped in the form of Fraser’s favourite subject, the lotus.

“I like the shape of the lotus and the endless capacity of meaning that can be attached to it, from love to strength to confidence,” she says. (Vicky Luthra)

“I like the shape of the lotus and the endless capacity of meaning that can be attached to it, from love to strength to confidence,” she says. (Vicky Luthra)

The 17 works on display are centered around the lotus in myriad forms as Fraser deconstructs, expands and contracts the flower in each of her canvases. She uses layers of handmade wasli paper, and pigments made from malachite and semi-precious stones from Jaipur.

Ask Fraser on why lotus continues to be a recurring motif in many of her shows including her solo, ‘The Sacred Garden’ in 2016, she says, “I like the shape of the lotus and the endless capacity of meaning that can be attached to it, from love to strength to confidence. It has the most extraordinary and beautiful shape and has sharp angles, circularity and angularity to it. It has contrasting ideas within its own nature.”

The golden lotus

The golden lotus Elaborating on how the word darshan translates into seeing and being seen by the deity, a common practice in Hindu worship, 52-year-old Fraser says, “In Indian sacred and devotional art, the eyes are the last elements that artists add to their creation, be it in paintings or sculptures. Right from the Chola bronze statue makers in southern India to the artists in Rajasthan who work on the traditional religious scroll paintings — the phads, eyes are always the final addition.” She says her aim is simple here. To be concerned with “inner landscapes rather than the external ones.”

Fraser explores the feeling of being up in the mountains and the pilgrimage trips many undertake in the Himalayas in Red Himalayas (2015), using the traditional mountain imagery in red interspersed with lotus petals at the centre serving as the “ultimate goal to be reached”. Creation, 2018, is an ode to the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics awarded to a group of scientists who found two neutron stars that had a collision, called kilonova, and that produced highly visible gravitational waves. The artist has tried to describe that event visually by using lotus petals to chronicle the spiraling light show and the explosion. Through some of the works, she has also chronicled how the lotus often, has been used as a tool for visualisation during meditation.

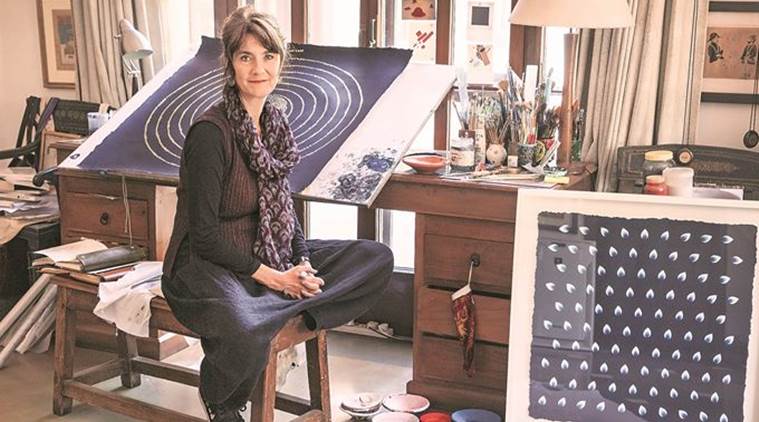

A few years ago, Fraser came across Gheranda Samhita, an 18th century Sanskrit text on yoga, where the yogi is asked to visualise “an island of jewels” where seven scented flowers perfume the surroundings. Jasmine and sthalpadma flower featured in the list. She was immediately intrigued by the concept of scent being used as a focus for meditation. The artist was also informed how the sthalpadma flower, which translates into “land lotus”, changes its colour during the day. It comes as no surprise that Fraser paints the lotus in varying shades of pink in Sthalapadma, 2017.

“I am interested in how artforms can influence each other and how we can translate one artform into another. For instance, how we can describe music in words or into paintings. Interestingly, unlike western alcohol-based perfumes, Indian oil-based perfumes intensify, increase and expand during the course of the day according to one’s body temperature. I wanted to bring that sense of expansion,” she says.

Fraser who arrived in India in 1989 with her husband, author-historian William Dalrymple, turned to Indian miniatures after 2005. She began by working with its masters in Jaipur and for a long time, pored over Nathdwara paintings of 17th and 18th century Rajasthan. This was very different from a course in modern languages at the Oxford University and later at Wimbledon Art College. “I have been looking at Indian miniature paintings and have been observing what imagery, colours and shapes mean here,” says Fraser, who also did not shut her eyes to the rest of the world. She’s interested in contemporary art and fond of works by artists such as British contemporary artist Damien Hirst and Anish Kapoor.

Doing what was left behind by her kinsman, James Baillie Fraser, who painted India, its monuments and landscape in early 1800s, Fraser had initially begun where James left off. James would hire local artists to contribute to the Fraser album, comprising Company School paintings that depicted people and their different castes, work and crafts. The ‘hybrid’ paintings employing a combination of western and eastern techniques then later formed a major chunk of Fraser’s early works in the early ’90s. Apart from making a pit stop at the Venice Biennale in 2015, her paintings are now housed in the collections across the UK, UAE, the US, France and Australia, among others.

The exhibition is on till June 26 in London at Grosvenor Gallery