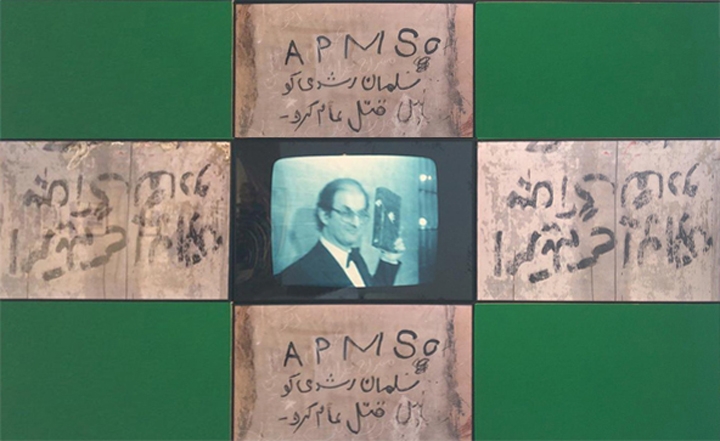

Over six decades, Pakistani-born and British-based artist Rasheed Araeen has dedicated his voice and work to the elevation of the Afro-Asian community he belongs to and the dismantling of the deep-seated neocolonialism within the Western art world. Since arriving in London in 1964, Rasheed Araeen’s efforts have spanned grassroots activities from joining the British arm of the Black Panthers in the 70’s to the founding of the postcolonial journal Third Text in 1987 to the curation of multiple group exhibitions (The Essential Black Art (1987) at Chisenhale Gallery and The Other Story (1989) at Hayward Gallery) as well as numerous letters that have been sent to Arts Council England and then prime ministers Tony Blair and David Cameron.

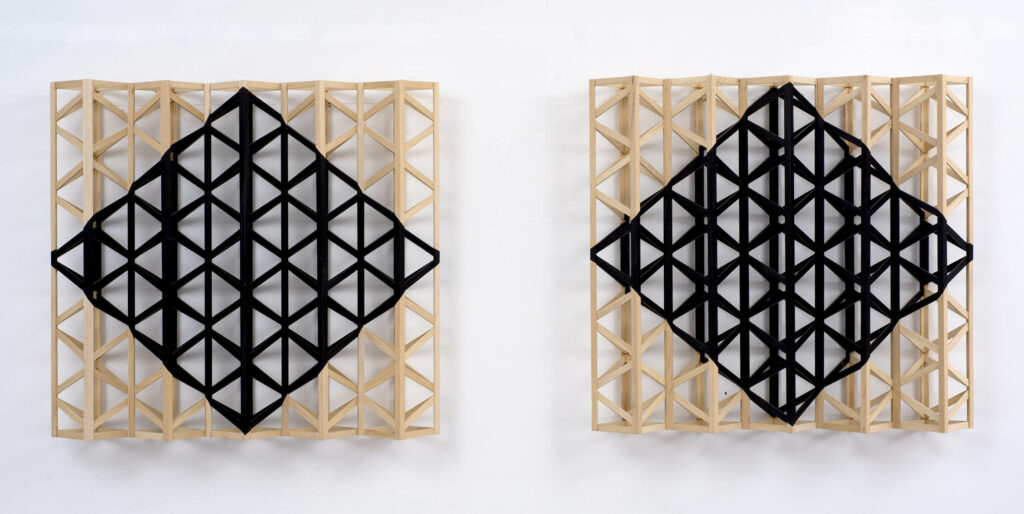

In his own body of work, Rasheed Araeen’s political and social convictions are embodied in Shamiyaana, which will be presented at Abu Dhabi Art in December 2021. Previously installed at documenta 14 in 2017 and a cafe in North London in 2019, Shamiyaana is positioned as a communal dining space for all. Besides the Indian-Pakistani finger food on the menu, the space is furnished with Araeen’s minimalist sculptures that also perform as tables while the walls are decorated with his geometric paintings and reliefs.

“Food is basic to life, and the way it is consumed by humans involves creativity,” says Rasheed Araeen. “My aim is to adopt this creativity and transform it into a work of art with the participation of those who are involved in the cooking and then eating it collectively.”

Below, Rasheed Araeen shares more details about his participation in the upcoming edition of Abu Dhabi Art in November 2021.

“My life has been a struggle against the establishment.” You said that during an interview with The Guardian in January 2020. Do you feel the same sentiments today more than a year later or have you reconciled with the past?

I’m still struggling against the establishment. It is a struggle against Eurocentrism for which the white artist is still central to modernism, and the artists of Asian and African origins are either treated as marginals or kept excluded from the mainstream. Although the situation has now somewhat changed with globalisation, as the art market now accepts artists from all over the world and they are promoted on an equal basis, the history of modernism is still exclusively of the achievements of white artists.

You have championed the contributions of Muslims, Blacks, Pakistanis among other minority ethnic and community groups in Britain. Do you feel there has been progress with regards to inclusiveness and representation in the art world?

Things have now changed. Artists from all over the world are accepted by the art establishment in the West. Moreover, many countries have now established or are developing their own art institutions, art galleries and museums, as well as their own art fairs and biennales. But, despite all this, the scholarship fundamental to the critical evaluation of art is still with the West, and thus the West continues to dominate and control the global art scene, as part of cultural imperialism.

Shamiana refers to an Indian ceremonial tent in the Bengali language. What was the rationale behind this choice of name for this artwork?

Shamiana is a sort of tent or marquee which is used for marriage ceremonies in the Indian subcontinent. I have the memory of marriages in my family in Karachi. A shamiana would be erected in front of our house in which guests would be welcomed and food served to them. These shamians were beautiful as they were decorated with colourful geometric designs. Alas, marriages no longer take place in these shamians. It is the memory of these bygone traditions of shamianas that is the basis of my artworks now called Shamiyaana. It was first created in Athens and now in London.

You’ve presented Shamiyaana at documenta 14 in Athens in 2017 as well as in London in 2019. Have you approached its installation different each time, depending on the occasion, city and audience?

When I was invited to participate in documenta 14 in 2017, particularly in Athens, it gave me an opportunity to fulfil my ambition to produce an artwork that would allow people to be part of it, not as an audience but as its creative participants or partners. Athens at the time was going through a crisis, not only of unemployment of its own people but it also had to receive immigrants and refugees particularly from the Middle East; and then to feed them. It was also the time and occasion when there would also be tourists, as well as audiences from all over the world for documenta.

The artistic aim of Shamiyaana was therefore to bring all these people together; in fact, under one roof where they would meet, eat together and engage in conversations. This was exactly what actually happened. People from all over the world, from different cultures and speaking different languages, tourists, art lovers or art audiences, refugees and immigrants, would meet the locals, rich and poor, sit at the same table and eat together; and, in fact, would try to talk to each other even when they could not speak and understand each other’s languages.

Shamiyaana was meant to be an open-ended and continuous artwork, but it could not fulfil this ambition in Athens. After four months, it had to be dismantled and put in storage, due to the limitations of finances and the non-availability of a place that would allow it to be continuous. According to an art theory by Adorno, it had to go into hibernation until the right time when it would resurrect itself. An alternative to this was to create another version so that it could maintain its continuity conceptually. It was on this basis that a new Shamiyaana emerged in London. It has a different structure and operates materially in a different way, but its aims and ambition are the same, conceptually.

What can audiences expect from you at Abu Dhabi Art?

The global art world today is dominated by art produced with ideas originating in the West. I don’t think it would be any different in Abu Dhabi. The aim of my work in Abu Dhabi is to depart from this dominant trend and present what is ‘Islamic’ but also modernist. It is not a kind of mixture that is common in the Arab and Muslim world but is an original modernist work that enunciates and celebrates the spirit of Islam. The audience of my work in Abu Dhabi should realize that there is no need for a Muslim artist to imitate or follow the West. There are enough ideas in the artistic traditions of Islam, which need not be imitated but can be reconstructed and renewed in the context of our modern world.

What would you like audiences to take away from their experience at Abu Dhabi Art?

I would like the audience to feel that Islam has its own ideas of aesthetics, art and beauty, which should be maintained and protected.

Abu Dhabi Art takes place from 17 November 2021 to 22 January 2022 at various locations across the city.